Most New Zealand soils are naturally deficient in phosphorus (P). On farmland, high production of animal and horticultural products exacerbates deficiencies if the phosphorus removed is not replaced. Therefore, the use of phosphorus based fertilisers is vital for the success of New Zealand agriculture.

Phosphorus and plants

Phosphorus is essential for any plant growth, storing energy and specific metabolic functions during the early stages of plant and root growth. Therefore, plants need a steady supply of phosphorus during germination and root growth, tillering, seed and fruit setting, and ripening.

Starter fertiliser is frequently applied when crops are sown to ensure a sufficient amount of phosphorus is available to the seedling. Different plants have differing requirements for phosphorus. Legumes, such as clover, require higher amounts than grasses.

Signs of deficiency

Plants with phosphorus deficiency will have:

- Poor seedling and root development

- Stunted top growth

- Spindly stalks

- Delayed maturity

- Low fruit production

- Clovers with poor nodule formation

Signs of deficiency are usually seen on older leaves first. If severe, the stem and leaves will show reddish-purple discolouring. Other factors, such as cold stress, can have similar effects, so a diagnosis should never be attempted based on visual appearance alone.

Phosphorus deficiency in animals

Animals generally don’t show obvious signs of phosphorus deficiency. However, when under physiological stress, e.g. after calving, animals that are deficient in phosphorus may show signs of:

- Reduced fertility

- Reduced weight gain (important for meat production)

- Reduced milk production (in dairy cows)

- Reduced mobility (dairy cows can go down with similar symptoms to milk fever)

Phosphorus loss

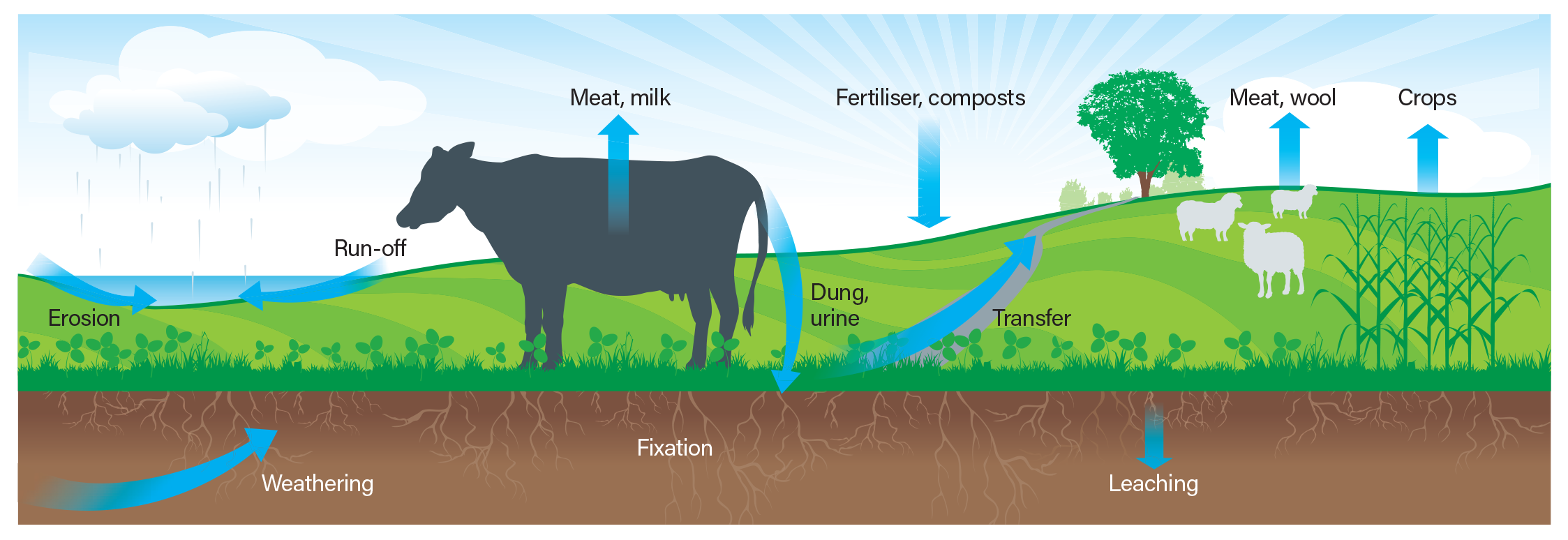

It is estimated that 80-90% of phosphorus applied to land is eventually used by plants. This means that the combined long-term losses of phosphorus are 10-20%. Phosphorus is added to the system through fertiliser, excreta and by the decay of plant material. It is lost primarily by run-off.

Phosphorus run-off

The major mechanism by which phosphorus is lost is by entering waterways, either dissolved in run-off water or bound to soil particles, e.g. by erosion (particulate-associated P - PAP). Increasing phosphorus levels in soil by applying phosphorus fertiliser increases the amount and concentration of both dissolved phosphorus and PAP.

Phosphorus leaching

In most soils, phosphorus reacts with certain minerals that prevent it from being lost by leaching. Phosphorus can irreversibly bind to some minerals, e.g. aluminium, iron and calcium. (This is different to phosphorus fixation, which is reversible).

In soil types that lack these minerals in the upper layers, phosphorus can move down the soil profile and leach from the root zone. Sands and podzols have the greatest tendency to leach phosphorus.

Soil tests

In New Zealand, soil phosphorus levels are usually measured with the Olsen P test. Other tests, e.g. the Truog, Bray and Resin P, have not been calibrated for New Zealand soils to the same extent as the Olsen P. Therefore, the Olsen P shows the best relationship between test results and plant growth in New Zealand soils.

One exception is when testing land that has been fertilised with reactive phosphate rock (RPR). The Olsen P test can not detect RPR residues, even though these will provide phosphorus for plants. One way to account for this is to multiply the Olsen P test result by 1.5 to 1.7; i.e. if the Olsen P result is 20, then for a soil fertilised with RPR, this is equivalent to an Olsen P between 30 and 34.

Alternatively, the Resin P test can be used. However, this has not been calibrated over a wide range of soils, so can be difficult to interpret in many situations.

The depth that soil samples are taken from varies depending on the crop: recommendations are 75 mm for pasture and 150 mm for crops such as brassicas, wheat and maize.

Animal health

If animals ingest phosphate fertiliser they can develop health issues, such as fluorosis. This is not caused by the phosphate, but by the fluoride found in phosphate fertiliser. To avoid this, grazing should not occur for three weeks after application or until 25 mm of rain has fallen (to wash the fertiliser particles from the leaf onto the soil).

Environmental issues

As most soils can store phosphorus, there is low risk of losses affecting the environment. However, phosphorus fertiliser should not be applied to waterways, water-logged soil or when heavy rain is expected. Apply after winter to minimise losses from run-off. It is only necessary to use split dressings if application rates are higher than 100 kg P/ha.

Figure 1

The major features of the phosphorus cycle on a pastoral farm

Download and read the full fact sheet

Understanding phosphorus on your farm

Most New Zealand soils are naturally deficient in phosphorus (P). On farmland, high production of animal and horticultural products exacerbates deficiencies if the phosphorus removed is not replaced. Therefore, the use of phosphorusbased fertilisers is vital for the success of New Zealand agriculture.